There used to be a time in baseball where hitting 100 mph as a pitcher was special. There’s a certain speed upon which the human eye literally doesn’t have enough time to process ball vs. strike when a pitch is thrown from 60 feet, and it’s theorized that inhibiting factor starts at about 100 mph.

Growing up, the images of Randy Johnson or Roger Clemens instilled fear in the hearts of batters strictly due to their arm’s velocity. Nowadays, if you’re a D1 pitcher that can’t hit at least 97, you better have a viscous slider or have ability to paint those corners.

The title of this first post mentions hypersonics. “Is he really about to start his blog off with comparing hypersonic weapons to America’s pastime?” You bet your ass I am. Because now if your military doesn’t operate hypersonic weapons, you might as well stay at home.

America’s history with hypersonic weapons is the perfect encapsulation of its lost decades of weapon development spanning back to the 90’s. If you’re unfamiliar, that’s a topic worthy of it’s own post (or, frankly, novel). In summary, America got embroiled in a Global War on Terror for 20 years where it focused its efforts on defeating IEDs, goat herders with AK-47s, and cave systems, while her enemies pursued research on how to defeat American aircraft carrier battle groups. In essence, the greatest military in the history of human existence got complacent, and because of that, it has witnessed it’s dominance gap in several areas of critical weapons research and development become not only narrowed but in certain fields fully surpassed.

Nothing embodies this series of events more than hypersonic missiles. When it comes to cruise missiles, drones, radar, fifth generation aircraft, and air defense, I could realistically paint a prettier picture of America’s dominance. Although the lead in these fields has been narrowed, I’d venture to take the debate stage and argue the Pentagon still holds the torch. When it comes to hypersonics, my argument breaks down. The Pentagon has found itself completely flat footed by the efforts of Russia and even more so the Chinese to the point it is now scrambling to field even a single program for operational use.

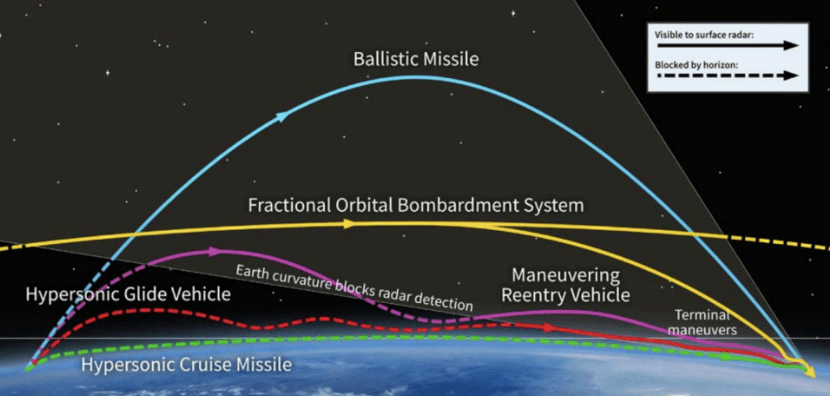

To take a quick step back, perhaps it’d be helpful to define exactly what makes something hypersonic. So, beyond just being a general’s favorite buzzword these days, the most common definition has to do with speed, specifically anything flying faster than Mach 5. However, this definition actually breaks down a bit. It’s not just speed, but the ability to maneuver at said speed. Technically speaking, the German V-2 rocket deployed during WWII traveled at hypersonic speeds, but no one would consider that more than an early ballistic missile. No, modern hypersonics require maneuvering re-entry vehicles. Whether that’s using fins, ducts, or some other control surface, your typical Cold War ICBMs don’t count.

Hypersonics, for the most part, can be separated into two categories: hypersonic glide vehicles (HGV) and hypersonic cruise missiles (HCM). The first are just as they sound, aerodynamic vehicles that re-enter Earth’s atmosphere after being powered up to hypersonic speeds from some other power source, typically a ballistic missile, and glide itself onto its target, maneuvering if necessary.

HCMs also need an external source to get it up to speed in order to function such as rockets or other aircraft. However, they utilize their own on board engine to maintain hypersonic speeds, commonly known as scramjets or ramjets. They will typically travel at slower speeds than HGVs, but because they have their on engine on board, maneuvering will be less taxing on them.

So why are they so sought after? Essentially, they are able to more easily defeat very expensive ballistic missile defense systems currently in play. Why? Well, if you venture back to that graphic above, ballistic missile trajectories are very easy to predict, and, therefore, intercept. 30 seconds after a ballistic missile is launched, a sophisticated radar can accurately predict its entire flight path. And if you can predict where a missile will be and when it will be there, you can intercept it. Hypersonics can maneuver mid-flight, therefore, making it much more difficult to intercept.

So why is this useful? They become an incredibly useful weapon if you need something very important destroyed in a very short amount of time, think strategic long range radar arrays, aircraft carriers, or command and control bunkers at the beginning of a conflict. If you suddenly need an enemy’s primary radar to be taken out to allow your other strike packages to safely engage other targets in the area, it’s useful to have a weapon that can reliably survive it’s flight onto said target.

Okay, so that’s out of the way.

I wanted this post to mostly focus on recent developments out of the September 2025 Chinese military parade, but I’ve now realized it may be impossible to discuss without proper context. I think a wider discussion on current hypersonic programs is a topic for a later post, so the immediate following are four newly presented missiles China graced the world with only a few short months ago.

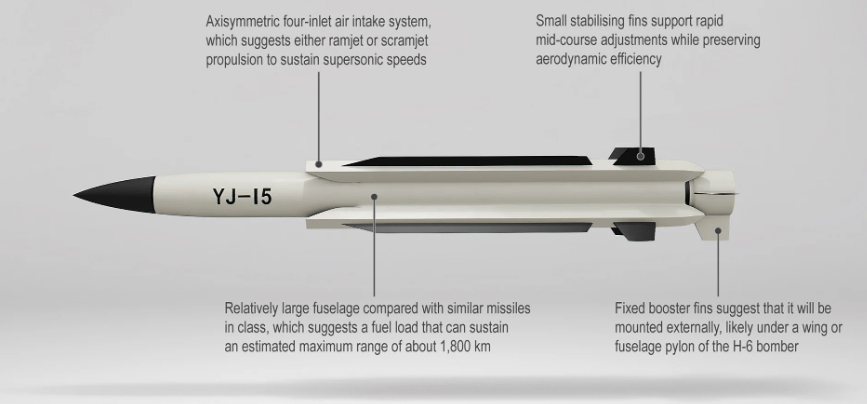

YJ-15

Among the first new anti-ship missiles that were revealed at the parade was the YJ-15, which appears to combine supersonic speeds with extended range to challenge traditional naval defenses such as gun-based close-in weapon systems (CIWSs).

Believed to be powered by a ramjet engine, the missile features an axisymmetric four-inlet air intake and a streamlined fuselage. This design enables the missile to sustain high-speed flight while minimizing drag.

The YJ-15 is estimated to have an overall length of about 6.5 m and a diameter of about 0.5 m. Given these dimensions, it likely weighs about 1,500 kg including a 200 kg warhead.

These physical characteristics, along with its compact stabilizing fins, suggest a configuration optimized for maneuverability during mid-course flight without the need for large deployable wings.

Given its physical characteristics and propulsion system, the YJ-15 is probably able to achieve speeds in excess of Mach 5, with an estimated range of between 1,200 and 1,800 km.

Furthermore, these characteristics and structural features suggest it is intended for air launch, most likely from the PLA Air Force’s (PLAAF’s) fleet of H-6 strategic bombers. This aircraft features the necessary clearance and reinforced pylons to carry such a weapon externally, and its operational profile aligns with China’s doctrine of long-range stand-off strikes.

Air-launch capability not only extends the missile’s effective reach but also provides flexibility in deployment, allowing PLAAF bombers to operate from secure bases while projecting power deep into contested maritime zones.

Operationally, the YJ-15 has likely been designed to engage high-value naval targets such as aircraft carriers and large surface combatants. Its supersonic speed and ability to execute evasive maneuvers during the terminal phase significantly reduce reaction times for adversary defense systems, complicating interception.

While primarily intended for maritime strike, the missile’s likely performance envelope suggests a potential secondary land-attack role.

The introduction of the YJ-15 underscores China’s commitment to strengthening its anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) posture in the Indo-Pacific. By fielding a weapon that combines speed, range, and flexible deployment options, the PLAN will enhance its capacity to deter or disrupt carrier strike groups and other surface forces operating within contested maritime regions.

YJ-17

The YJ-17 features an elongated, needle-like nose that has likely been engineered to minimize wave drag and reduce thermal stress during atmospheric re-entry and sustained hypersonic flight.

This sharply tapered forebody also helps maintain laminar flow at extreme speeds, ensuring stability while reducing the heat load on the missile’s leading edges.

The absence of any visible air intake confirms that the YJ-17 does not employ air-breathing propulsion like a scramjet but instead relies on a solid-fuel booster for its initial acceleration before transitioning to an unpowered glide phase.

This is a configuration that is typically employed by boost-glide weapons, which exploit altitude and velocity to achieve extended range without continuous propulsion.

The YJ-17 is estimated to have an overall length of about 9 m and a diameter of about 0.5 m. The missile’s fuselage is smooth and uninterrupted, and this reduces aerodynamic drag and radar cross-section. It will likely be able to achieve maximum speeds of between Mach 5 and Mach 8.

Unlike subsonic cruise missiles that feature large deployable wings for lift, the YJ-17 employs a waverider design, generating lift from the shockwaves created at hypersonic speeds. This approach allows the missile to maintain altitude and maneuver without sacrificing velocity.

Small, rear-mounted control surfaces on its warhead provide fine adjustments during glide, enabling the missile to execute unpredictable lateral movements and skip-glide maneuvers in the upper atmosphere. These control surfaces have likely been incorporated to provide the YJ-17 with the ability to evade interception by complicating tracking and disrupting targeting systems of missile defense systems.

The YJ-17 has likely been designed with thermal protection measures incorporating advanced heat-resistant composites and ablative coatings to withstand temperatures associated with flights that occur between Mach 5 and Mach 8.

The missile’s overall length and diameter indicate compatibility with vertical launch systems (VLSs) on large surface combatants such as Type 055 destroyers, as well as external carriage by China’s fleet of H-6 bombers.

This versatility in deployment reflects a design philosophy aimed at integrating the YJ-17 into multiple strike platforms, reinforcing China’s layered maritime denial strategy.

Operationally, the YJ-17 will likely be deployed to deliver precision strikes against high-value naval targets such as major surface combatants, amphibious assault vessels, and aircraft carriers.

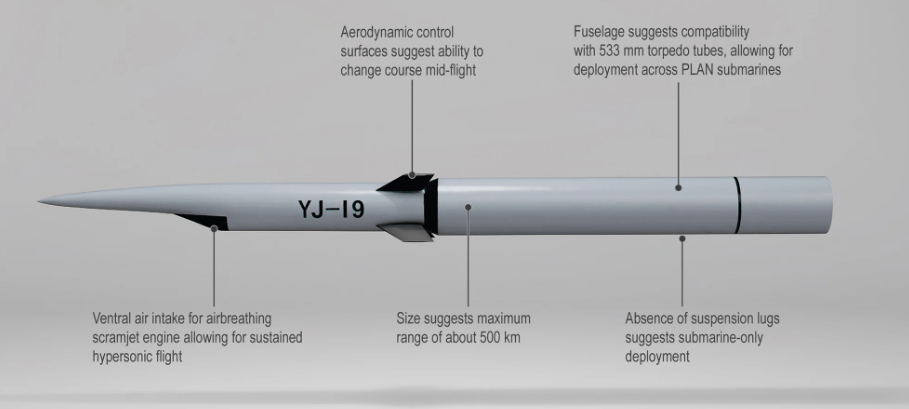

YJ-19

Among the new missiles revealed at the parade, the YJ-19 was perhaps the most visually striking given the lack of weapons with a similar form factor within China’s present arsenal.

The weapon’s nose section is particularly distinctive given its apparent attempt to accommodate a scramjet intake system while maintaining a highly aerodynamic profile for hypersonic flight.

Unlike conventional missile noses that are typically sharp or ogival for drag reduction, the YJ-19 features a slightly blunted, integrated intake configuration that channels airflow more efficiently into the scramjet engine.

In terms of its physical dimensions, the YJ-19 is estimated to be about 6 m in overall length with a diameter of about 533 mm, matching the constraints of submarine torpedo tubes.

Its overall weight is believed to be around 2,000 kg, including the warhead. These dimensions and physical attributes suggest that the YJ-19 can achieve speeds between Mach 5 and Mach 10, with a range of approximately 500 km.

Central to the YJ-19’s design is its scramjet propulsion system, which appears to have been designed with fuel efficiency considerations while allowing the missile to maintain extreme velocity throughout its trajectory.

The streamlined fuselage and ventral air intake are characteristic of hypersonic architecture, while small stabilizing fins provide the agility required for mid-course maneuvers.

Given these physical attributes, the YJ-19 has likely been conceived to provide the PLAN with a hypersonic missile that is endowed with the stealth advantages associated with submarine deployments.

With its ability to be deployed from standard 533 mm torpedo tubes, it is likely that the YJ-19 will eventually be integrated across the PLAN’s fleet of in-service submarines.

Deployment of the YJ-19 is expected to focus on strategic maritime zones, including the South China Sea and Western Pacific, where control of sea lanes is central to regional security dynamics.

By combining the stealth of underwater launch with hypersonic speed, the missile compresses adversary reaction times and complicates interception efforts.This capability significantly enhances China’s ability to disrupt deployment plans of its adversaries’ surface fleets, posing a formidable challenge to carrier strike groups and other high-value naval assets.

The introduction of the YJ-19 also signals China’s growing proficiency in hypersonic technology, placing it among a select group of countries capable of fielding submarine-launched hypersonic cruise missiles.

When viewed alongside other systems such as the YJ-21 air- and ship-launched anti-ship missile and the DF-17 land-based ballistic missile, the YJ-19 signals China’s intention to adopt a layered approach to maritime strike, combining long-range ballistic options with agile, high-speed cruise missiles.

YJ-20

Another new missile revealed at the parade was the YJ-20, which appears to combine advanced aerodynamics, hypersonic propulsion, and precision guidance capabilities.

It features a biconical design, and this suggests a multistage configuration compatible with VLSs on major surface combatants such as the Type 055 destroyer.

While official specifications are undisclosed, assessments indicate a large missile with substantial payload capacity, indicating a role as a strategic asset in China’s naval arsenal. It has an overall length between 8 and 10 mand a diameter between 80 and 120 cm.

In terms of its propulsion system, the YJ-20 likely employs a solid rocket booster for initial acceleration, transitioning to a scramjet engine for sustained hypersonic cruise.

Given this propulsion configuration and its form factor, the estimated speed of the YJ-20 likely lies between Mach 6 and Mach 7 during cruise, with terminal velocities potentially reaching Mach 9.

This performance, coupled with an estimated operational range between 1,500 and 2,000 km, enables deep strike capability across the Indo-Pacific theatre.

The weapon’s guidance likely consists of an integration of BeiDou satellite-based navigation systems, active radar homing, and imaging infrared seekers, ensuring resilience against electronic countermeasures and precision targeting of high-value assets.

With these characteristics, the YJ-20 will be a cornerstone of China’s A2/AD doctrine given its ability to penetrate layered defenses and deliver kinetic energy at hypersonic speeds, making it exceptionally difficult to intercept with current missile defense systems.

The YJ-20 will also play a large part in the PLAN’s strategy to counter aircraft carriers in the region, underscoring the service’s long-held ambition to alter the regional balance of power by challenging US and allied naval dominance.

Integration into the Larger Force

These four developments add to an already mind-boggling stockpile of hypersonic missiles the Chinese military currently employ. It was already well known the People’s Liberation Army (PLA i.e. Chinese military) had at its disposal the DF-21D (the carrier killer), DF-26, DF-17, DF-27 (the Guam Killer), and the YJ-21.

I would argue the issue here isn’t necessarily the U.S.’s ability to intercept these various weapons. In both the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and Ukraine, American made weapons have time and again proven the technical feasibility to defeat these types of threats. I would venture to think the Pentagon’s fear is two-fold: (1) the shear amount of weapons that have been produced thus far and (2) the range of platforms these threats can be launched from.

For the first fear, we’re talking about missiles in the thousands. Current American ballistic missile defense possesses stockpiles of THAAD and SM-3 at a combined ~1,000 interceptors for both sea-based and land-based assets. When you take into account that these interceptors would be launched at decoys as well as 2-for-1s to guarantee successful intercepts, American missile defense falls woefully short. This is the type of shortfall that will lose you a war. If within the first 8 hours of conflict China is able to obliterate the airbases at Guam and Japan, as well as negate any aircraft carrier advantage, you’re talking about Randy Johnson trying to pitch Game 7 with a 15 lb. weight strapped to his arm.

Now is usually the time where an analyst provides the solution. I don’t have one. And neither does the Pentagon. The current best course of action could be a variety of strategies: (1) significantly increase the rate of production on interceptors (2) disperse your Pacific assets to as many hard to hit air bases as possible (3) produce strategic long-range strike assets that can destroy enemy launchers before missiles are airborne (4) pray.

The correct path is to employ all aforementioned strategies, but that doesn’t solve the huge elephant (RIP Alabama football) in the room: China’s ability to mass produce these weapons at rates the world has never seen. That’s an issue that will take a WWII herculean effort to solve.

-

Really enjoyed this. The baseball analogy hooked me right away and made a complex topic feel intuitive. The missile breakdowns were easy to follow without feeling dumbed down, and the point about production scale being the real problem hit hard. Solid analysis—looking forward to what you write next.

LikeLike

-

loved your analysis. Easy to read and understand for novices like me. Enjoyed the sports references.

LikeLike

-

Leave a comment